[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

I gave a talk at “Spilbar” at the National Film School of Denmark yesterday titled ”‘I’m just playing’; the radical act of expecting nothing in return” (follow link for my presentation), where I made an attempt to connect some of the thoughts and questions I’ve been wrestling with for a while now. As is most often the case, I hadn’t really thought this all the way through, but I really appreciated the opportunity to think out loud in public.

For the occasion, I had made up the (rather depressing) notion of the “ROI society” to describe our collective obsession with “return on investment”. It’s like our current era is almost defined by the desire to always get something in return and the belief that no action is worth undertaking unless it pays off in some way. I consider this a scourge of contemporary society, a flaw (even if it’s a feature, not a bug) causing great misery.

Here’s the sad face I put up whenever I think of ROI:

A performance measure used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment or to compare the efficiency of a number of different investments. ROI measures the amount of return on an investment relative to the investment’s cost. To calculate ROI, the benefit (or return) of an investment is divided by the cost of the investment, and the result is expressed as a percentage or a ratio (Investopedia)

The ROI mentality is evident everywhere in society: in politics, in private companies, public institutions, in education, in the arts, culture, from Kindergarten to University, from we’re born till we die. While I don’t pretend to know exactly how we got ourselves into this mess, the toxic cocktail of neoliberalism and New Public Management certainly contributed greatly:

We have been induced by politicians, economists and journalists to accept a vicious ideology of extreme competition and individualism that pits us against each other, encourages us to fear and mistrust each other and weakens the social bonds that make our lives worth living (George Monbiot)

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

When we’re all learning to think and act in a specific way, this eventually trickles down into every aspect of our lives, and play suffers as well. In my work, it’s one of the most frequently formulated dilemmas: is play a legitimate purpose or should we harness its ”magic” for other ends? Can play enhance learning? Creativity? Innovation? Efficiency? Loyalty? Motivation?

Maybe it can, but should it?

I’m not saying we should never consider returns, outcomes, rewards (or money for our labor), of course, but I’m merely proposing that we shouldn’t do it all the time. We shouldn’t accept living in a ROI regime and we’d benefit massively from also doing things just for the sake of doing them. The same goes for play. Play can have hugely important side effects, but we risk losing sight of play itself if all we care about are these side effects. If we only see play as meaningful when it has an externally defined ”purpose” or goal, we’ve already misunderstood the very nature of play.

This far, it is all a bit (too) sad, but hey, there’s hope. There’s always hope. While play is clearly suffering from ROI, play is probably also the best antidote we have. To fight the ROI dragon, we must do the opposite of what it dictates, we must embrace play as a legitimate and legitimately rewarding activity in itself.

What do we do, then? How do we turn hope into action? We have to believe that play matters. That ”just playing” is not only ok, but the initial, revolutionary act we can all take.

Probably the biggest roadblock to play for adults is the worry that they will look silly, undignified, or dumb if they allow themselves to truly play. Or they think that it is irresponsible, immature, and childish to give themselves regularly over to play. (Stuart Brown)

The first step for the resistance, then, is to, quite simply, play. Find ways of playing that appeals to you and jump right in. Experiment, goof around, take yourself less serious, join forces with other people, see how you feel about it and what really gets you in a good, playful mood. Take my friend Lynn, for example. Based around the #oneplaything hashtag on Twitter, she arms herself with chalk, heads out into the world, starts playing and embraces where that takes her (even when it snows):

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.0.91″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CounterPlayLeeds-1701-Medium.jpg” show_in_lightbox=”off” url_new_window=”off” use_overlay=”off” always_center_on_mobile=”on” force_fullwidth=”off” show_bottom_space=”on” /][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

Now that you’re volunteering for the cause of the playful resistance and want to do more, you can become a play activist, taking play to the streets, inviting more people to play, cultivating communities of play in the process. Finally, we can insist on the possibility of living playfully, making play a “life practice”, an approach to everything we do – as my friend and perhaps my single biggest source of inspiration, Bernie DeKoven, has been demonstrating for decades:

“playfulness is an even more liberating way of being than play itself, more, well, freeing. More, in fact, revolutionary.”

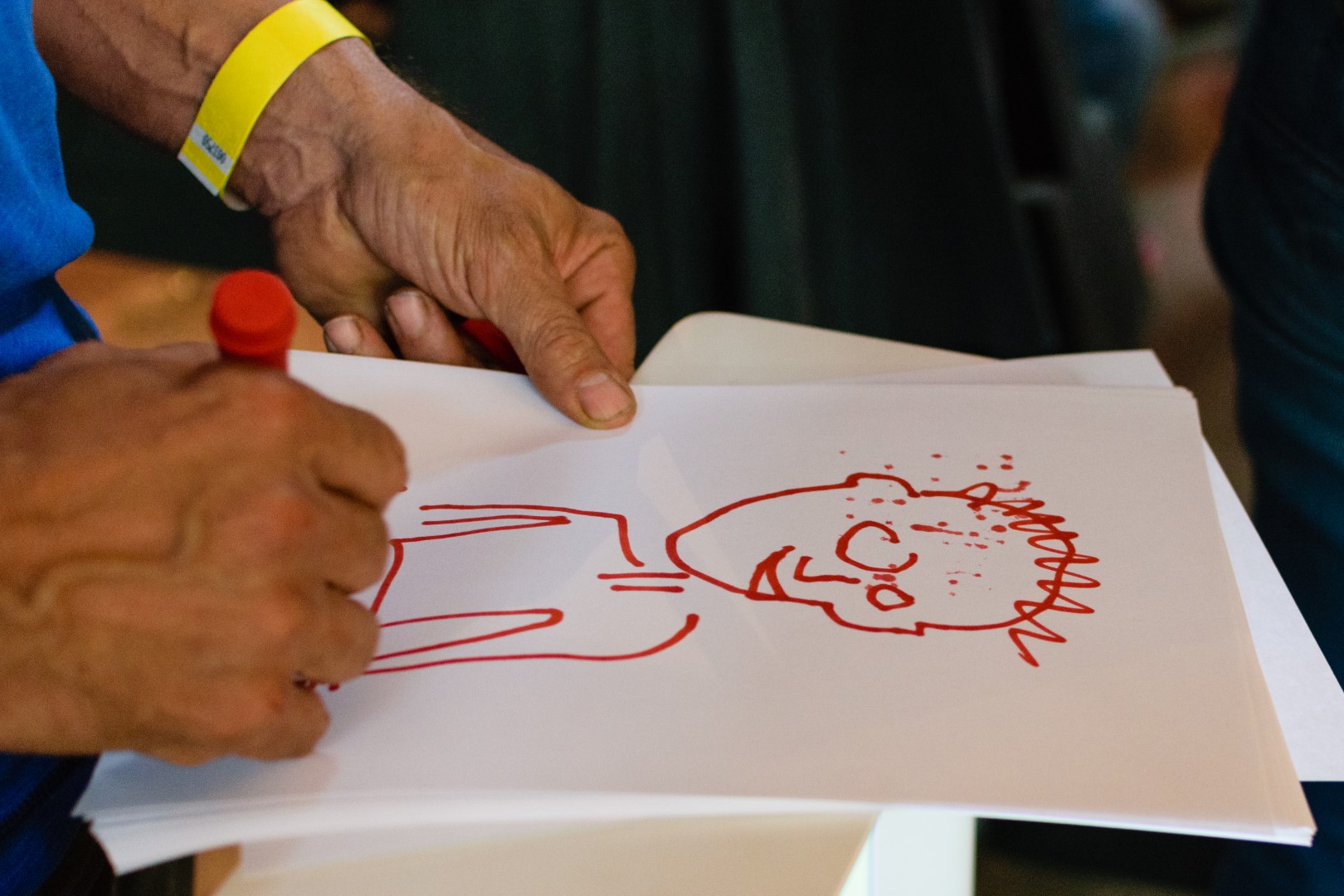

We shouldn’t forget to make the love visible. Play is a manifestation of love, and we shouldn’t hesitate to show it to the world. As someone (Jim Thompson, if I’m not mistaken) wrote during CounterPlay Leeds:

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.0.91″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CounterPlayLeeds-1866-Medium.jpg” show_in_lightbox=”off” url_new_window=”off” use_overlay=”off” always_center_on_mobile=”on” force_fullwidth=”off” show_bottom_space=”on” /][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

Tell the stories, stand tall, be proud. Don’t fear the weirdly widespread idea that playing is for kids or that it makes you less worthy of respect. It’s the other way around. If you dare to break the mold, challenge the common perceptions and show a different path through life, you’re a hero in my book.

When we muster the strength and courage to pursue play in this way, something almost magical happens. In play, we negotiate meaning and purpose, we explore possibilities and other ways of being, and, as Miguel said yesterday, in play we create worlds. We imagine and develop worlds within the world and these worlds are not inconsequential, they are not entirely detached from what we tend to call “the real world”:

When people agree on the terms of their engagement with one another and collectively bring those little worlds into being, they effectively create models for living (TS Henricks)

There’s a massive, transformational, even revolutionary potential, in just playing. This immense power can’t be predictably controlled, but I think, nonetheless, that there are some things that will happen more often than others.

“When we are playing together, despite our differences, we celebrate a transcendent sameness, a unity that underlines the illusion of our separateness. You could call this an act of love – an enacted love that lets us keep the game going. Many acts of love, in fact, many acts of compassion, caring, trust, assurance.” (Bernie DeKoven, A Playful Path)

Play cultivates “togetherness”, as it allows us to create and negotiate special conditions for being together. This is a connection I should have made clearer at Spilbar: the social dimension, the ”togetherness of play”, is not something I want to somehow artificially ”force” play to do, it’s what happens when play thrives and is allowed to develop on its own terms.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

This all resonates with an analysis made by George Monbiot, when he argues that we should develop a new, big and compelling political narrative around a sense of belonging:

“But by coming together to revive community life we, the heroes of this story, can break the vicious circle. Through invoking our capacity for togetherness and belonging, we can rediscover the central facts of our humanity: our altruism and mutual aid. By reviving community, built around the places in which we live, and by anchoring ourselves, our politics and parts of our economy in the life of this community, we can restore the best aspects of our nature.”

This is also the central theme in a book by Lynne Segal I’m currently reading, which bears the absolutely wonderful title ”Radical Happiness: Moments of Collective Joy”:

As the world becomes an ever lonelier place, it is sustaining relationships, in whatever form they take, which must become ever more important. An act of defiance, even.

It is very important to be aware that Segal is highly critical towards what has been called the “happiness industry” by William Davies and others:

Today there is a booming field of management research on positivity at work, all designed to keep employees working longer, with corporations such as Google even installing play equipment in their workplaces. Yet Spicer argues that what he calls ‘the cult of compulsory happiness’ can actually render workplaces more miserable, since the implicit ban on negative sentiment often proves ‘emotionally stunting for employees’, especially in difficult situations, by preventing them from expressing the full range of their emotions.

Play equipment at Google is what I have previously called “playwashing” and clearly in line with ROI thinking – no doubt Google expect a return on their investment. This is *not* what I’m advocating for.

Even so, there’s a dilemma here: set play free, play without expecting ”returns on your investment”, but consider how it might change all of society for the better? Yeah, at this point, I felt obliged to state the obvious: there’s a fine line to walk between acknowledging the inherent value of play on its own terms and the instrumentatlisation I’m so deeply concerned about. It would be overly ironic if I end up turning play into an instrument to fight instrumentalisation, right?

I think I’m onto something here, and that play is an essential component in any good life, but even if I’m wrong, what do we have to lose? A world where more people get to play more and live more playful lives? I can live with that. It gives me the same vibe as this classic:

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.0.91″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/hoax.jpg” show_in_lightbox=”off” url_new_window=”off” use_overlay=”off” always_center_on_mobile=”on” force_fullwidth=”off” show_bottom_space=”on” /][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.91″ background_layout=”light”]

During the Q&A and afterwards, it became evident to me that I should have more clearly said that while I’m interested in all kinds of play, I’m aiming to design spaces and create opportunities for a particular kind of play – let’s, for now, call it positive play or hopeful play. I celebrate the diversity of play and I insist that we embrace as broad a spectrum of play as possible, but as I describe in the “CounterPlay Manifesto”, “we do maintain that some ways of perceiving play are more beneficial and meaningful than others”.

Anyway, it was all a bit rough around the edges, just like this post, but let me know what you think. Does it make sense? Am I disrespecting play while pretending to defend it?

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

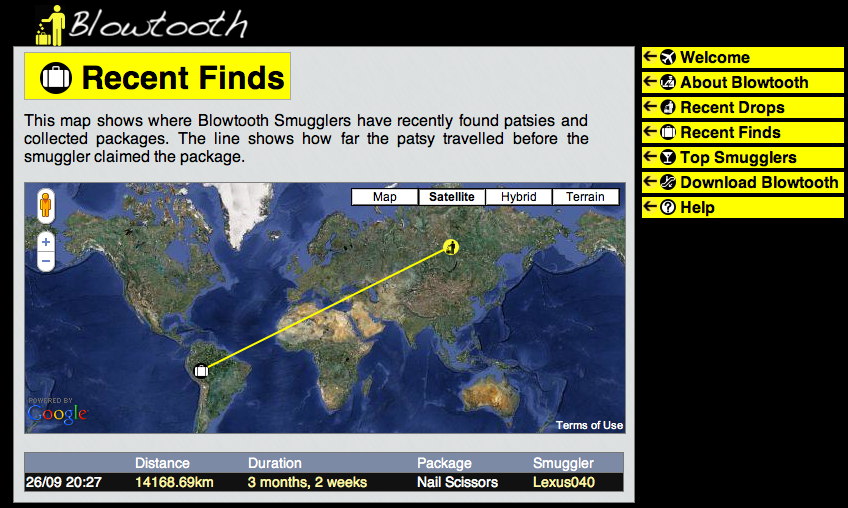

FearSquare

FearSquare