[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

[toc]I am writing this post in response to the call issued by Mathias in his blog post, to “collect and share bits and pieces that demonstrate the power of play to play with power.” I agree that we live at an interesting moment, when it is worth considering whether and what kind of potential lies in games to inspire a challenging of power, and a critique of power structures. I have been involved with a number of projects that have specifically set out to play with power, or to critique power in playful ways, and this post is an opportunity to connect together the dots of those projects. I’ll start with a little bit of relevant theory and then move on to some examples from games and from my own research.

Turning a lens on how power is enacted

Ian Bogost makes an argument in his book, “Persuasive Games: the expressive power of videogames,” that the unique experiential characteristic of game playing, the one that is not available with other media, is the requirement of the player to carry out procedures. For example, in a truck driving game, such as Euro Truck Simulator, you’re not simply told about a truck driver, you act as a truck driver making decisions under the constraints that a truck driver typically operates under. You take orders for deliveries, collect trailers full of food and other goods, and drive those goods to far away parts of Europe, following a GPS system, obeying traffic laws and earning money for on-time delivery. Interestingly, sometimes, when you are running low on funds, you find that you need to break the speed limit in order to make the delivery in time.

According to Bogost, a game can make a powerful argument by requiring your participation in a task, upon which you can later reflect. Instead of being told that truck drivers operate in circumstances that encourage dangerous driving, we experience that pressure ourselves, and understand the importance and power of economic concerns in the day to day decisions of truck drivers. Playing a game makes us act out the argument that it is trying to communicate. It makes us complicit in that argument. In this way, games can make arguments that are very subtle. They can help us understand why people make decisions that initially may seem to be lazy, or dangerous, or against their own interest. The player is placed in a difficult situation, where in order to manage their resources in a strategic manner, they are forced to make decisions of which they would otherwise disprove.

There are some very good examples of games that make these types of procedural arguments. Papers, Please places the player in the role of a border official, who must check the documents of immigrants:

As the game progresses, government rules over documentation change regularly and the border official must approve more and more documents per day in order to support the needs of their family. We understand better after playing the game, how these officials make errors, but also why they are often open to bribery. In effect, this game makes an argument about power – instead of blaming the corrupt and stupid border officials, we learn to blame the difficult circumstances that they have been placed under. In the game 3rd World Farmer we are forced to make decisions such as whether to accept toxic waste to be dumped on our land in order to pay for medicine for a sick child. We realise that, given the pressures faced and the resources we have, that there is essentially no solution, or winning condition to this game.

This section shows how games can make very subtle arguments about the way in which power is enacted. It can turn our attention away from blaming individual human errors, and onto understanding and criticising systemic pressures that those people experience in their lives.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Blowtooth” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Blowtooth – playing with airport security

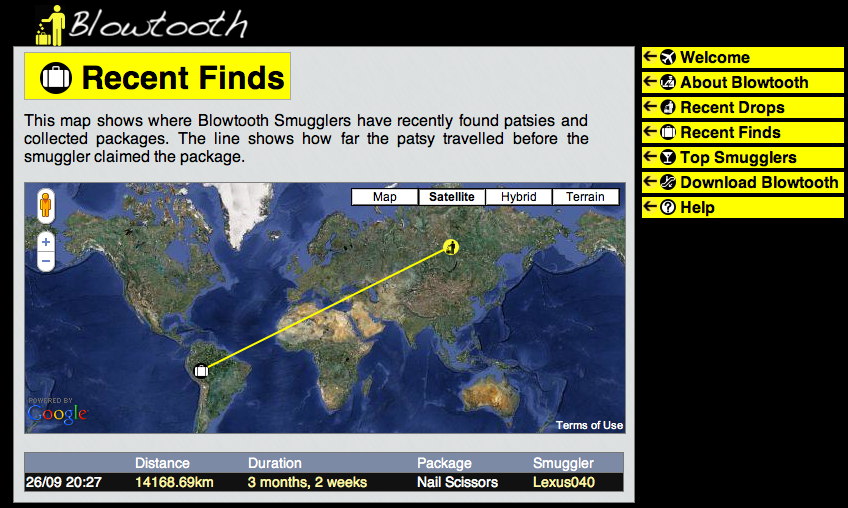

Blowtooth is a game developed by Ben Kirman in collaboration with myself and Shaun Lawson, when we all worked together at the University of Lincoln. It is a location-based game that asks players to smuggle virtual drugs through real airport security. The intention of the game, unlike those discussed above, is not to engender empathy in the player for real drug smugglers, but rather to direct attention on the security apparatus of the international airport.

As we write in the paper:

Blowtooth is specifically designed to exploit the affordances of international airports: environments in which people are subject to particularly high levels of intrusive surveillance and security monitoring.

Airports have been described as constituting the most authoritarian facility designed for the use of free civilians, an authoritative structure rivalled only by army bases and maximum security prisons. Kellerman describes the movement of passengers through the various security checks imposed by airport authorities in great detail [8] and discusses the impact of these checks on the experience of the international traveller. Throughout this analysis he draws attention to the ubiquitous presence and power of authority figures and the effect of causing tension and anxiety amongst travellers, staff and officials alike (see also [18]). Indeed, airports are places in which oppressive control technologies are implemented and people’s expectations of privacy are altered. Authorities have extra powers to search and detain individuals and there are different expectations on travellers’ behaviour than would be expected outside of this context.

Thus, through asking the player to act as a drug smuggler, Blowtooth invites the player to more closely examine the security and power structures of the airport – something that most travelers have come to take for granted. Indeed, a quick study demonstrated that Blowtooth provoked participants to think more critically about both the nature of airports, and the idea of playing games in high security environments,

If you wish to read more about this project, the paper is available for free here.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” disabled=”off” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Fearsquare – critiquing the “transparency” agenda

FearSquare is a website / hack / game developed by Andy Garbett, along with Ben, Shaun and myself, and was later the source of much interesting discussion with Jamie Wardman, and expert in risk communication. FearSquare was developed in response to the decision by the UK government to release crime statistics monthly, at a street-by-street level of detail, as both an interactive map and an easy-to-use API. The release of this map was advertised as a move towards improving transparency in public services. However, as academics, we were very concerned about the social and psychological effects of generating an easily searchable map of all crimes in the UK. For example, what does this information do to those people who find themselves in a “red” zone? What about their house prices and their public services? What about the decisions of people making journeys – will they avoid red zones? Essentially, we were worried that this crime map would become a force that would encourage ghettoisation. It has the potential to further inequality. Thus, we created a playful response in the form of FearSquare.

FearSquare is a website / hack / game developed by Andy Garbett, along with Ben, Shaun and myself, and was later the source of much interesting discussion with Jamie Wardman, and expert in risk communication. FearSquare was developed in response to the decision by the UK government to release crime statistics monthly, at a street-by-street level of detail, as both an interactive map and an easy-to-use API. The release of this map was advertised as a move towards improving transparency in public services. However, as academics, we were very concerned about the social and psychological effects of generating an easily searchable map of all crimes in the UK. For example, what does this information do to those people who find themselves in a “red” zone? What about their house prices and their public services? What about the decisions of people making journeys – will they avoid red zones? Essentially, we were worried that this crime map would become a force that would encourage ghettoisation. It has the potential to further inequality. Thus, we created a playful response in the form of FearSquare.

FearSquare is an application which allows FourSquare users in the UK to easily see the official crime statistics for the places where you ‘check-in’. The intention is to give you a uniquely individual look at the levels and types of crimes you are exposed to in your daily life. Fearsquare provides users with personally contextualized risk information drawn from UK government ‘open data’ crime maps cross-referenced with check-ins from the location-based social network Foursquare.

Apart from providing crime statistics information for the places that you visit, FearSquare uses some simple game mechanics in an attempt to invert the rhetoric of the UK Crime Map. Players are given a score based on the “danger” level of their check-ins. Leaderboards are created, which reward players with more consistently “dangerous” check-ins. The intention here was to subvert the argument of the map (i.e., that some places are dangerous and should be avoided) by offering rewards for visiting those places, and through doing so undermining the power of those statistics.

Fearsquare was successful in engaging users for a variety of reasons, including, humour and novelty as well as provoking reflection on important societal issues regarding ethical, social and psychological questions underlying interaction with technology and open government data. Our observations of tweets of this, more critically engaged, nature demonstrated that some users were prompted to think and reflect more deeply and concertedly about the wider issues resulting from use of Fearsquare, digital crime maps and CMC-R (Computer Mediated Communication of Risk).

Leaderboards were also created for the most dangerous check-in locations. Hilariously, a police station was consistently the most dangerous place in the UK, due to a quirk in how some crimes are reported.

If you wish to read more about this project, the paper is available for free here.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Epilogue

This post is probably long enough at the moment, but before finishing I will just point to another few projects that involved some form of playing with power, which readers may find interesting.

The paper “Games Against Health” critiques the many recent examples of “games for health” – suggesting that this trend is an essentially neo-liberal one, where government places personal responsibility for healthy living on the citizen in place of providing health care services.

The paper “CHI and the future robot enslavement of humankind: a retrospective” uses an intentionally playful tone to speak directly to the HCI research community about their own responsibilities in ensuring human agency in technologies.

I’ll finish with another quote from Mathias’ blog post: “play is powerful because it invites us to play with power.” I’m very interested to read further examples of people playing with power.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”References” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

References:

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. MIT Press.

Linehan, C., Kirman, B., Lawson, S., & Doughty, M. (2010). Blowtooth: pervasive gaming in unique and challenging environments. In CHI’10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2695-2704). ACM.

Garbett, A., Wardman, J., Kirman, B., Linehan, C., & Lawson, S. (2014). Fearsquare: hacking open crime data to critique, jam and subvert the ‘aesthetic of danger’. In Proceedings of Korean HCI conference 2014.

Linehan, C., Harrer, S., Kirman, B., Lawson, S., & Carter, M. (2015). Games against health: a player-centered design philosophy. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 589-600). ACM.

Kirman, B., Lineham, C., & Lawson, S. (2012). Exploring mischief and mayhem in social computing or: how we learned to stop worrying and love the trolls. In CHI’12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 121-130). ACM.

Kirman, B., Linehan, C., Lawson, S., & O’Hara, D. (2013). CHI and the future robot enslavement of humankind: a retrospective. In CHI’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2199-2208). ACM.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

In the best case, these games provide people with a much needed break, whereas in the worst case it is used to disguise or sweeten what could perhaps most accurately be described as exploitation; Mere sugarcoating on an otherwise unacceptable proposal, a means of coercion to make people work harder and more. Yes, the games can be a first step in a more playful direction, and they can certainly be part of an ambitious playful strategy (I recall the notion of “

In the best case, these games provide people with a much needed break, whereas in the worst case it is used to disguise or sweeten what could perhaps most accurately be described as exploitation; Mere sugarcoating on an otherwise unacceptable proposal, a means of coercion to make people work harder and more. Yes, the games can be a first step in a more playful direction, and they can certainly be part of an ambitious playful strategy (I recall the notion of “