[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.19.2″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.19.2″][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.19.2″ parallax=”off” parallax_method=”on”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

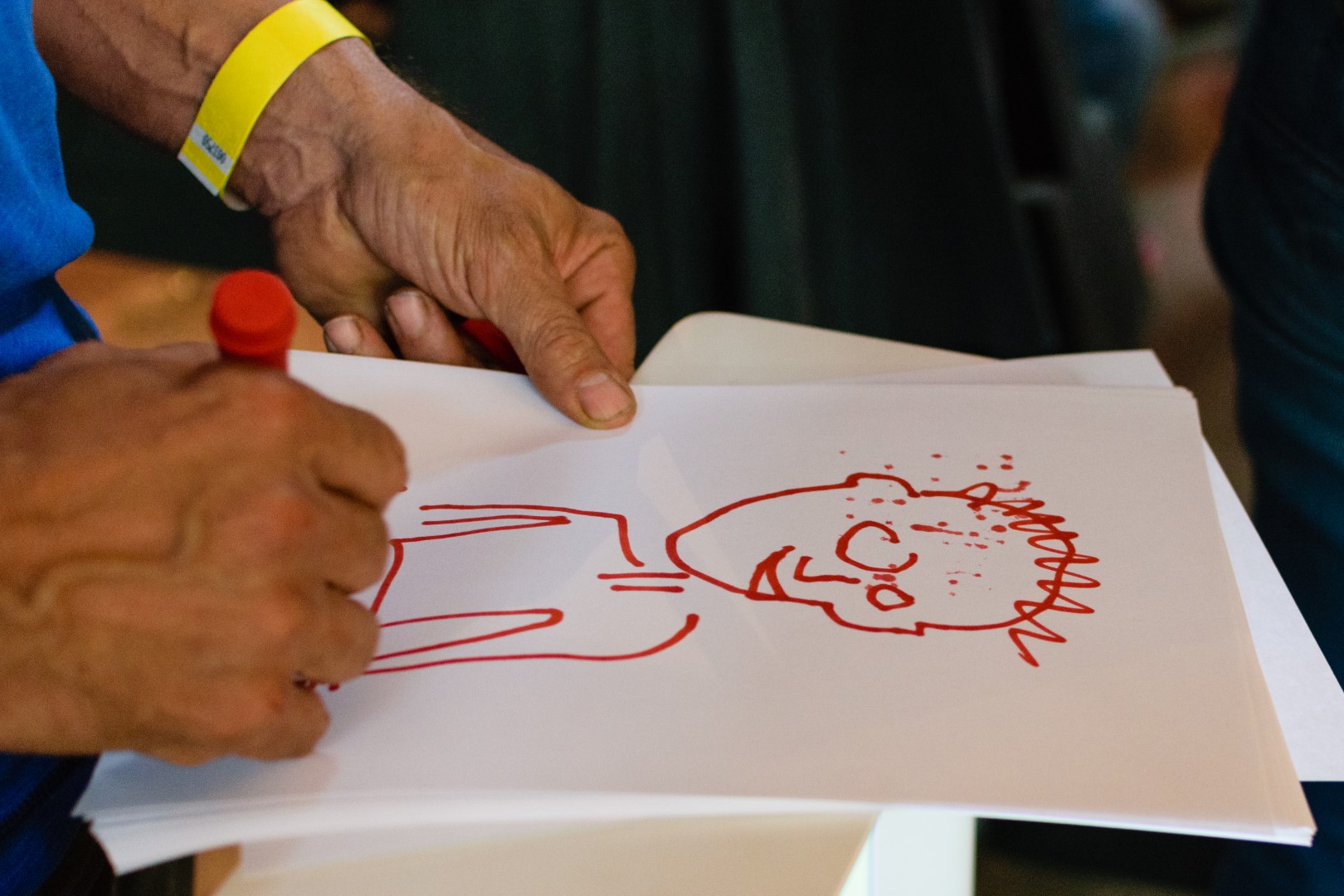

For nylig var jeg af BUPL Nordsjælland inviteret til at bidrage på en pædagogisk temadag i Hillerød, der havde fået titlen “Sæt legen i centrum“. Det var en skøn formiddag med en masse leg, refleksion og samtaler om leg. Sikke dog en herlig flok dygtige, engagerede pædagoger (og nogle andre, relaterede fagligheder), der i den grad vil legen, og som har mod på at tage livtag med de små og (meget) store udfordringer, de møder hver dag.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_toggle title=”Dagens program:” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

9.00-9.15: Velkomst og leg

9.15-9.45: Oplæg: Leg, fællesskab og demokrati

9.45-10.15: Fælles refleksion og samtale om leg

10.15-10.45: Leg

10.45-11.00: Pause

11.00-11.15: Læreplaner – udfordringer og muligheder

11.15-12.00: De næste skridt

[/et_pb_toggle][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Vi startede med at genopfriske den vigtige §7 i den nye dagtilbudslov, hvor legen beskrives som “grundlæggende”:

“Dagtilbud skal fremme børns trivsel, læring, udvikling og dannelse gennem trygge og pædagogiske læringsmiljøer, hvor legen er grundlæggende, og hvor der tages udgangspunkt i et børneperspektiv.”

Der er en øget opmærksomhed på legen lige nu, og det bør vi fejre og glæde os over, men det kræver samtidig en stor indsats af alle parter, hvis de gode intentioner skal slå igennem i den pædagogiske praksis. Det kræver, at vi finder sammen i stærke “legefællesskaber”, hvor vi kan støtte og inspirere hinanden, mens vi med et kor af stemmer insisterer på legen, også som et fænomen, der vitterligt har værdi i sig selv.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Leg, fællesskab og demokrati

Jeg præsenterede mig, som jeg jo efterhånden har for vane, som legeaktivist, der vil gøre (næsten) hvad som helst for at få legen til at trives i samfundet. Derefter beskrev jeg hvordan jeg oplever at blive radikaliseret i disse år, hvor jeg modsætter mig “nødvendighedens politik” og i stedet insisterer på noget så uhåndgribeligt som håb og drømme. Det er især leg som livspraksis, der optager mig, og jeg arbejder ud fra en stor og umulig tese, der siger at:

Leg er ren livsglæde, legende mennesker lever bedre liv i en kompleks, uforudsigelig verden, og samfund hvor leg trives er også samfund hvor mennesker trives

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Slideshare” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Skal jeg fremhæve noget fra fra mit indledende oplæg om leg, fællesskab og demokrati, så må det være legens demokratiske potentiale. Eller måske snarere legens demokratiske natur.

Demokratiet er jo højt prioriteret i loven om dagtilbud, og det hedder blandt andet at:

”Dagtilbud skal give børn medbestemmelse, medansvar og forståelse for og oplevelse med demokrati. Dagtilbud skal som led heri bidrage til at udvikle børns selvstændighed, evner til at indgå i forpligtende fællesskaber og samhørighed med og integration i det danske samfund”

Og vi finder noget lignende i folkeskolens formålsparagraf (som i mine øjne også kalder på mere leg):

“Stk. 3. Folkeskolen skal forberede eleverne til deltagelse, medansvar, rettigheder og pligter i et samfund med frihed og folkestyre. Skolens virke skal derfor være præget af åndsfrihed, ligeværd og demokrati.”

Hvordan kan vi øve os i demokrati? Det kan vi selvfølgelig ved at lege med hinanden. Som den amerikanske legeforsker, Thomas S. Henricks, påpeger, så forhandler vi i legen med hinanden måder at leve sammen på:

“When people agree on the terms of their engagement with one another and collectively bring those little worlds into being, they effectively create models for living”

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BUPL-4852-2-2-Large.jpg” _builder_version=”3.19.2″][/et_pb_image][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Disse “frie forhandlinger” kan selvfølgelig sagtens føre til sammenstød og gnidninger, som man skal lære at håndtere for at kunne blive demokratisk medborger:

”Dagtilbud er et socialt fællesskab, hvor alle er deltagere og lærer at navigere i konflikter og håndtere dem”

Her er det vigtigt, at børn (og voksne) lærer at praktisere det, Helle Marie Skovbjerg kalder “kvalitetsstridigheder”:

”Kvalitetsstridigheder er præcis dem, der gør, at man pludselig kan vise egne ideer til legen bedre, fordi man må insistere på dem, eller når man pludselig møder andres positioner og opdager, at de er interessante eller udfordrende. Stridighederne åbner med andre ord ens øjne for, at tingene kunne være anderledes.”

Det kalder på legekompetence, som det fremhæves hos Herdis Toft:

“At lege godt kræver stor legekompetence blandt udøverne. Opøvelse i legekompetence er samtidig opøvelse i demokrati”

Her talte vi om, hvordan man støtter børns udvikling af legekompetence på måder, der ikke underminerer legen. Det blev også påpeget, at børn har forskellige forudsætninger for at blive kompetente legere, og at nogle børn har brug for mere støtte end andre, når pædagogerne møder dem i dagtilbud og skole (ligesom med så meget andet, kan man sige).

Det er måske værd at tage med, at Herdis i øvrigt forholder sig temmelig kritisk til mulighederne for, at denne “opøvelse” faktisk kan foregå i dagtilbud og skoler:

“Dette anerkendes ikke i dag af de statsligt styrede institutioner, som danner ramme om børns leg. Tværtimod forsøger man ofte at styre de legendes ustyrligheder ved at sætte regler op, som ikke står til forhandling. Man modarbejder den demokratiseringsproces, som det ellers er institutionens erklærede mål at fremme”

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BUPL-4868-9-2-Large.jpg” _builder_version=”3.19.2″][/et_pb_image][et_pb_text admin_label=”Dømmekraft” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

For faglig dømmekraft

Det der bliver afgørende for, at alt dette kan bringes i spil, og at legen kan trives, det må være den faglige dømmekraft hos den professionelle, myndiggjorte pædagog. I sidste ende er det pædagogen der, sammen med børnene, må afgøre hvad der giver legen – og børnene – de bedste muligheder for at trives.

Heldigvis taler man i “Master for en styrket pædagogisk læreplan” også om det faglige råderum:

“De brede pædagogiske læringsmål skal derfor formuleres, så det pædagogiske personale sikres et fagligt råderum. Det faglige råderum skal være båret af pædagogisk begrundede valg af metoder og tilgange og praksisnære evalueringsredskaber, som fremmer en faglig refleksion over læringsmiljøet”

Det er der grund til at glædes over, men det sker næppe af sig selv, det er noget, man må insistere på, lokalt og på tværs af dagtilbud og skoler. Det er også (men absolut ikke kun) en kamp, som den enkelte pædagog må deltage i!

Igen ser vi en parallel til legen, for ifølge Lars Geer Hammershøj, så er netop dømmekraft en særlig kraft i legen:

”Også i legen får man idéer med en pludselighed og spontanitet, som ikke kan styres. Den gode leg er kendetegnet ved, at dem, der leger, er gode til at bidrage til legen med noget interessant. Det kræver dømmekraft at vide, hvad der kan bidrage til legen og udvikle legen, så den bryder med det, man kender eller har gjort før”

Både når man skal være en god “leger”, en god pædagog og en god demokratisk medborger, så er dømmekraften altså afgørende.

Måske skal vi huske Gregory Batesons linedanser: “Linedanseren opretholder sin stabilitet ved ustandselige korrektioner af sin ubalance”. Det kræver både øvelse og dømmekraft at være en god linedanser, der hele tiden justerer sin indsats efter alle de mange sanseindtryk hjernen modtager – præcis som når vi leger. Svaret er aldrig givet på forhånd, men vejen findes i et samspil af mange faktorer, som man i situationen må vælge mellem.

Jeg viste lidt af denne fine video, “Den store opdagelsesrejse for de helt små“, hvor (desværre nu afdøde) Kjetil Sandvik siger noget klogt om dømmekraft og læringsmål:

“man skal ikke være så forhippet på, at det hele skal være i rammer, og planlagt ud fra læringsmål, men at man kan bruge den frie leg, og så kan man bagefter hive sine læringsmål frem og se, “jamen ramte vi nogen af dem” og så vil man nok se, at man ramte pænt mange.”

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”YouTube” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=11&v=jryxDLc4lLc

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Vi drøftede også dokumentation og evaluering, som begge er vigtige, men som også kan risikere at komme i vejen for legen. Det hedder sig jo, at “en styrket pædagogisk læreplan må nødvendigvis være båret af en tydelig og ambitiøs dokumentationspraksis og en systematisk evalueringskultur.”. Det er der ikke i sig selv noget galt med, så længe det ikke bliver for tungt, stift og ødelæggende for spontaniteten og muligheden for at se det smukke i øjeblikket. Dokumentation og evaluering bør altid være sekundært og blot et (af mange) middel til at skabe bedre vilkår for børnenes trivsel, udvikling og liv. Måske skal vi tale mere om “nysgerrighedskultur”, for egentlig handler det vel om, at vi skal være systematisk nysgerrige på, hvad der giver mening i den konkrete, lokale sammenhæng, og bør have en åben, undersøgende praksis, der fastholder og bygger på det meningsfulde.

Spørgsmål og gode idéer:

Til allersidst bad jeg alle om at skrive (mindst) én post-it med et spørgsmål, de ville diskutere med deres kolleger eller en idé, de ville gå hjem og prøve af. Også her var det meget tydeligt, hvor meget alle de her legesyge mennesker har på hjerte.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BUPL-4876-13-2-Large.jpg” show_in_lightbox=”on” admin_label=”Post-its” _builder_version=”3.19.2″][/et_pb_image][et_pb_toggle title=”Se blot alle de spørgsmål der blev stillet, idéer der blev skabt og intentioner der blev delt:” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Sætte fokus på hvorfor vi gør som vi gør som pædagoger?

Forældre på banen ift. at lege med deres børn.

Tilbage til at lege ligesom i “gamle dage”.

Demokrati og leg

Hvordan kan vi inddrage og informere forældrene?

Voksne som rollemodel

Hvordan understøtter vi de spontane elementer i en leg i stedet for at fokusere på rammer og regler?

Hvordan bliver voksne de bedste rollemodeller for udvikling af leg?

Mere fokus på at legen er en værdi i sig selv.

Formidle hvor god og givende legen er til forældrene.

Er legen grundlæggende?

Hvordan vi fagligt får formidlet at leg giver social kompetence

Hvordan får vi de udsatte børn mere med i legen – så de udvikler deres legeglæde?

Hvordan får vi fanget ungernes kreativitet, fantasi og opfindsomhed til at starte LEG?

Hvordan kan vi som pædagoger være med til at sætte legen i højsædet? Vi skal insistere!!!

Hvordan skal pædagoger tale (råbe) om legen?

Fokus på legens værdi for både børn og voksne

Vi vil have mere kreativ tænkning og opfindsomhed. Børn skal være med til at sætte dagsordenen i klubben.

Jeg vil forsøge at lave det legende alternativ i undervisningen.

Hvordan skaber jeg/vi et legelaboratorie i skolen?

Skabe modstand, insistere på at der ikke kun findes én vej, et opgør med nødvendighedens politik

Fra måling til faglig vurdering?

Legen i skolen, i fagene, i fritiden

Tage det alvorligt at legen er grundlæggende og starte der, når man fx skal arbejde med læringsmål.

Hvordan imødekommer skole/SFO børns behov for leg?

Leg på dagsordenen på personalemøder, forældremøder, temaaftener.

Tage leg op på vores P-møder til videre diskussion og refleksion.

At være medskaber af legeuniverser.

Skal alle kunne lege?

Hvordan kan vi se, at børnene leger godt?

Udvikle lege(lærings)miljøer 🙂

“Fri leg” – hvad er det?

Husk nysgerrigheden!

Hvordan insistere på det faglige råderum og den faglige dømmekraft?

Det fungerer bedst, når vi som voksne er med og er tilstede!!

Slip kontrollen i legen.

Gør noget nyt, gør noget andet 🙂

Pædagogen som linedanser

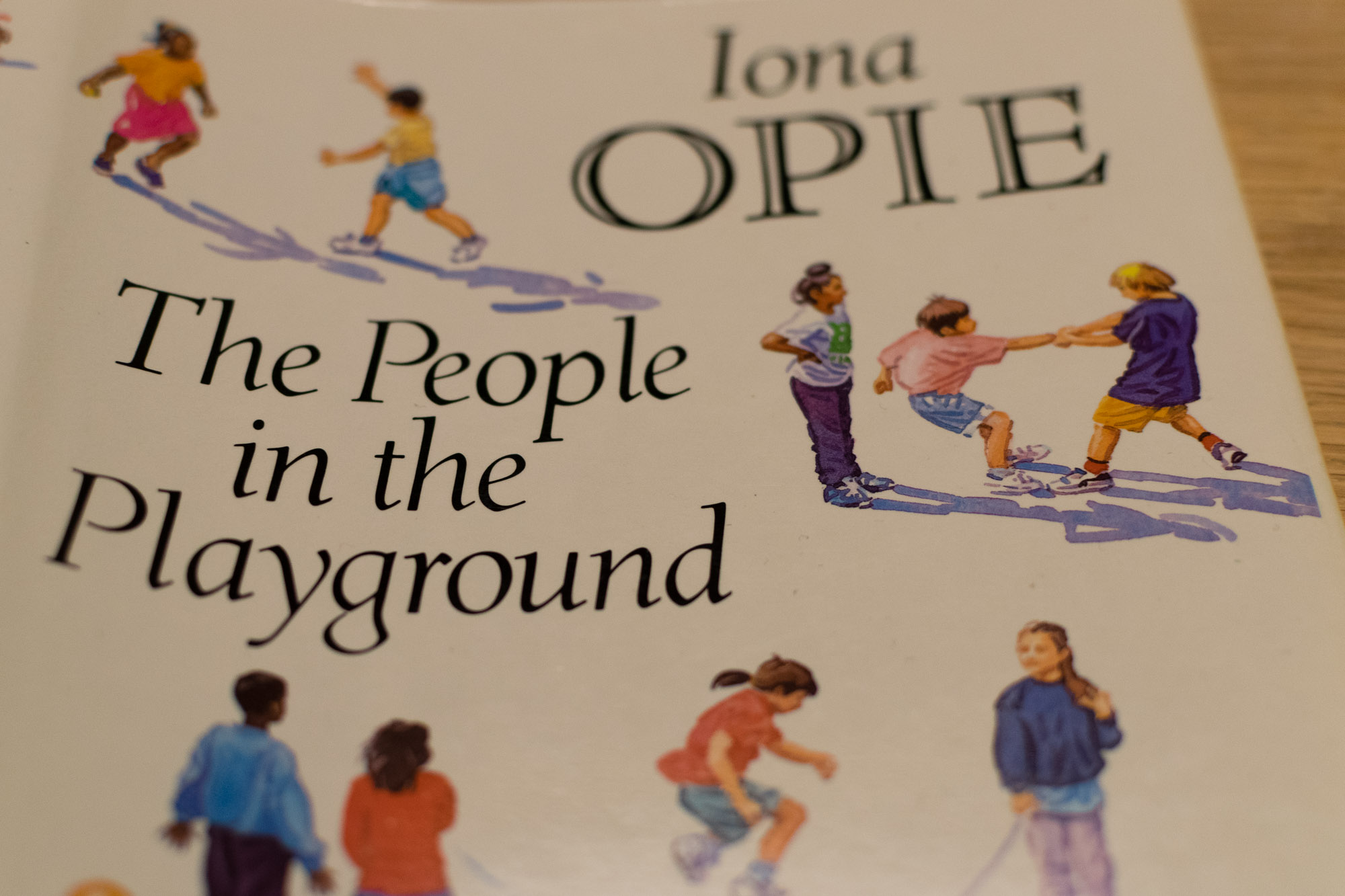

Vi skal overlevere alle de gamle fælleslege til børnene. De lærer dem ikke af sig selv.

Hvor meget skal voksne (lærere, pædagoger og forældre) bestemme børns legerelationer og med hvilket formål?

Slip kontrollen!

[/et_pb_toggle][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.19.2″]Der er jo, mildest talt, nok at tage fat på, og jeg håber, at bare nogle af disse spørgsmål bliver stillet og nogle af intentionerne bliver realiseret i den kommende tid.

Især håber jeg, at der bliver kæmpet for det faglige råderum og den professionelle dømmekraft, så der bliver plads til legen med al dens uforudsigelighed, spontanitet og glæde – og jeg vil selvfølgelig gøre hvad jeg kan for at bidrage til den kamp.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_toggle title=”Lege vi legede:” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Hilseleg: Hver deltager giver hånd og hilser på en af de andre deltagere, og må først give slip på hånden, når de har fat i en tredje persons hånd.

Babbling eller “Pludre, plapre, sludre, skvadre, vrøvle”: Deltagerne taler sammen, to og to, om et vilkårligt emne. Den ene taler i 30 sekunder, og så den anden. Man skal ikke tænke for meget, men bare plapre løs.

What has changed?: Deltagerne stiller sig op på to rækker overfor hinanden, og ser godt på den person man står overfor. Den ene rækker vender sig rundt, mens dem i den anden række ændrer noget ved sig selv. Nu skal den første række vende sig om igen, og gætte, hvad den anden person har ændret.

Colombian Hypnosis: Den ene er hypnotisør, og hypnotiserer den anden til at følge sin hånd, der holdes op foran den hypnotiseredes ansigt.

Prui

[/et_pb_toggle][et_pb_toggle title=”Links og tekster” _builder_version=”3.19.2″]

Hansen, D. R. og Toft, H.: Ustyrlighedens Paradoks

Jensen, V. B.: En Kraft i legen og dannelse (med Lars Geer Hammershøj)

Møller, H. H., Ida Halling Andersen, I. H., Kristensen, K. B. og Rasmussen, C. S.: Leg i Skolen

Niss, K.: Til forsvar for nysgerrigheden

Poulsen, M.: Det Legende Menneske som Dannelsesideal

Poulsen, M.: Demokratiske Legelaboratorier

Skovbjerg, H. M. : Perspektiver på Leg

Toft, H.:Leg som ustyrlig deltagelseskultur – eller fortællingen om det demokratiske æsel

[/et_pb_toggle][et_pb_image src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BUPL-4873-12-2-Large.jpg” _builder_version=”3.19.2″][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]