[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.15″]

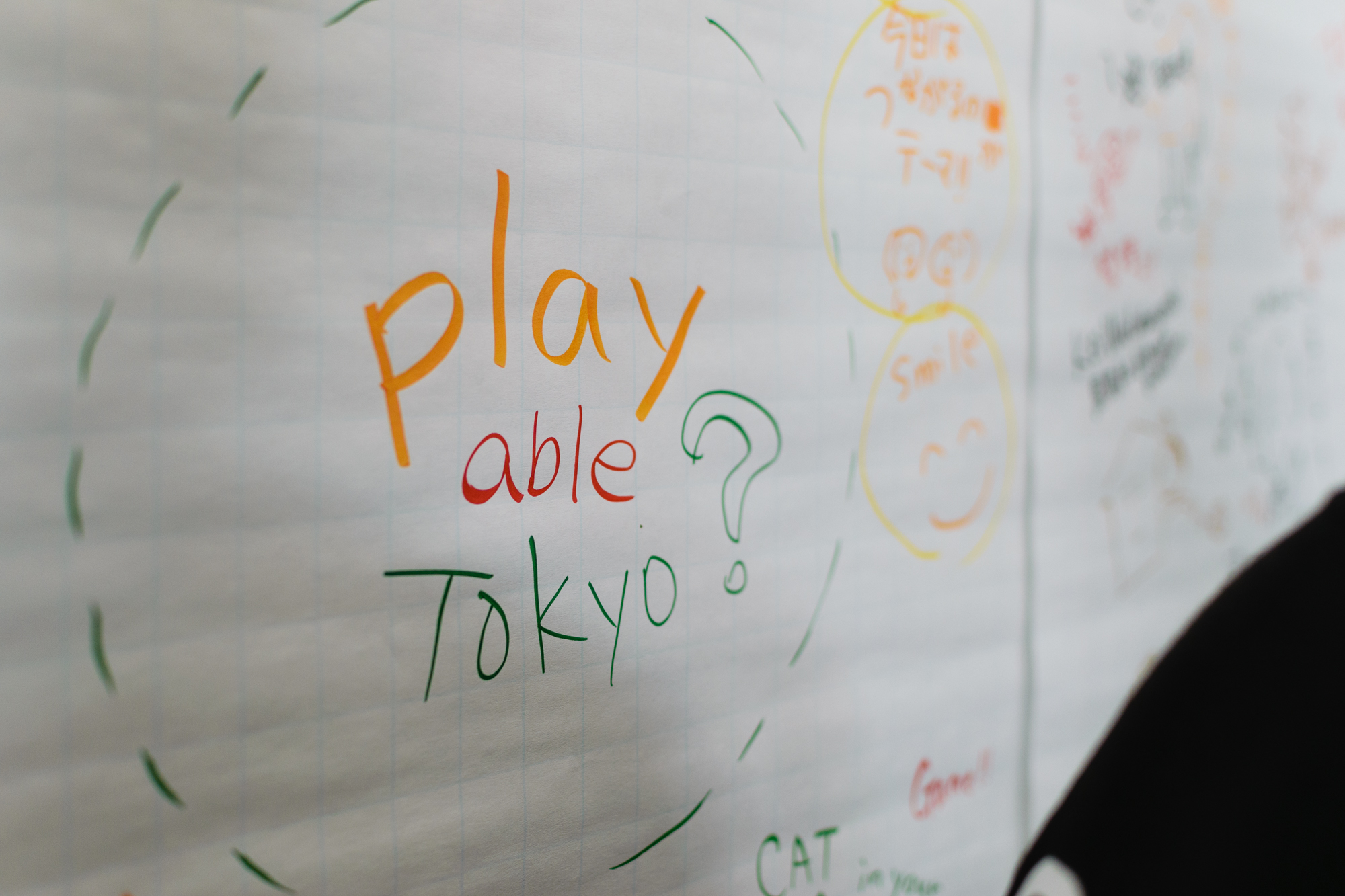

I try to embrace every possible adventure I stumble upon. Immer ein Abenteuer. When the nice, brilliant people at Playable City invited me to speak at their conference in Tokyo, I jumped with joy.

“Would you come over and talk about your work with play communities?”

Since that just happens to be my favorite topic, the answer was a resounding YES, of course.

It’s a few weeks ago now, and all the many, many impressions from the conference (and Tokyo in general) have had time to settle in.

There were a good blend of inspiring talks by Kei Wakabayashi, Motoko Tanaka, Tine Bech and Jo Verrent from Unlimited, as well as workshops organised by members of the “Creative Producers International” programme (see the full timetable here).

It was deeply fascinating to explore some of the cultural differences between Japan and Western Europe (like the way use public parks!), but also to be reaffirmed in our shared desire to play. I maintain that play reminds us of everything we have common as humans, all the similarities that we often tend to overlook. When we play together, the differences fall away, and we’re able to just be in and extend that moment together.

I would have appreciated more to talk and play, since it was all over so fast. Maybe more than one day the next time? It’s hard to get really deep into the more substantial questions and conversations in such a fairly short time, but other than that, it was a blast.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.15″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PlayableCityTokyo-2464-Large.jpg” /][et_pb_text admin_label=”Play community talk 1″ _builder_version=”3.15″]

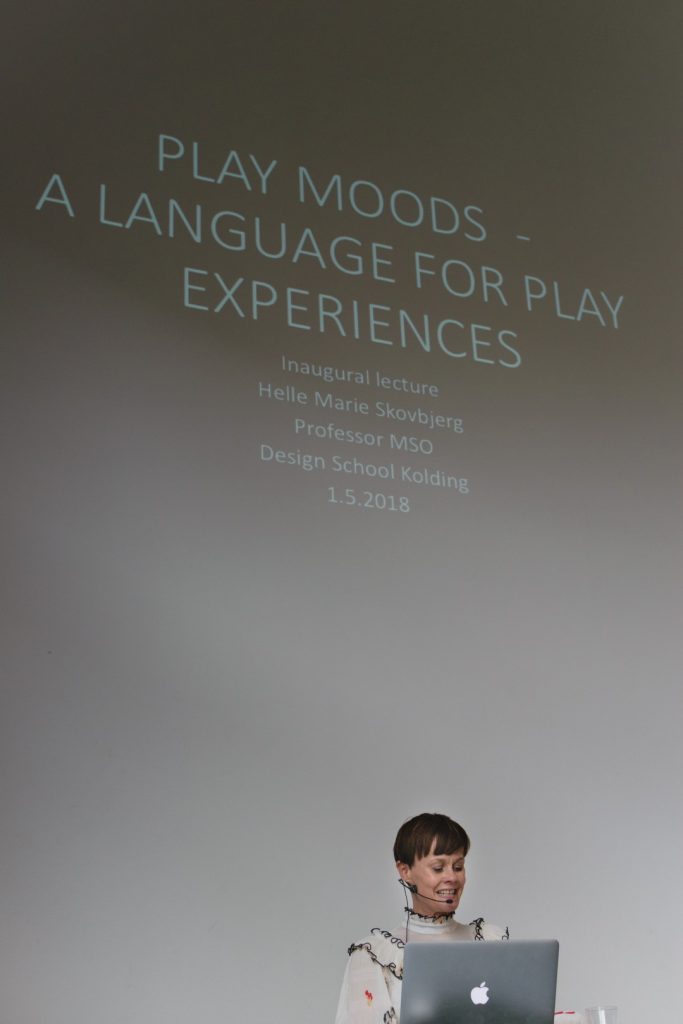

My own talk was basically an attempt to convey my deep love for the play community (you can download a pdf of my presentation)

The assumptions underpinning all my work are the ideas that we all have a desire to play, and that playful people are better equipped to live in this complex, weird and chaotic world.

We can all become more playful, and the best way to practice is to simply play. If play serves any greater purpose, it is helping us reconnect with our inherent playfulness (I wrote a little bit more about that in “Play to Live“).

It’s almost impossible to make play thrive unless it is embedded in a friendly play community. As I wrote in our book, “The Power of Play” on “The Global Play Community“:

“Cultivating a diverse play community where people are actively participating to explore and spread play is probably our best bet to foster a strong movement towards a more playful world. When we know for certain that we are not alone that other people feel the same urge to be playful, then we can easier muster the courage that is necessary to challenge the non-playful structures around us.”

Now, I can’t talk about play communities without acknowleding how much I’m drawing on Bernie DeKoven’s work (which is a lot). He’s gone now, sadly, but throughout his life he explored the true meaning of play and the communities where play flourishes:

“But we are a play community, and playing the way we do, for fun, for everyone’s fun, in public – our fun little community becomes something else. To those who want to be seen as people who embrace life, embrace each other, embrace spontaneity, freedom, laughter; we are an alternative. An invitation. We play as if the game isn’t important. The rules aren’t important. As if the only really important thing is each other”

This resonates with Lynne Segal’s writing in “Radical Happiness: Moments of Collective Joy“:

”As the world becomes an ever lonelier place, it is sustaining relationships, in whatever form they take, which must become ever more important. An act of defiance, even”

What can be more helpful in “sustaining relationships” than playing together? Especially if every single act of play takes us deeper into the play community, while also extending the invitation for people on the outside to join.

If you’re still with me, let’s say we agree that yes, play and play communities are indeed important, but how do we cultivate them?

I don’t have a simple recipe, but rather a handful of somewhat intangible, demanding pieces of advice. There’s no reason to pretend that it’s easy, because, well, it’s not. It’s a lot like love in that regard. It’s complicated, it takes a lot of effort, and there are no guarantees or predictable outcomes, but we probably can’t live without it.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.15″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PlayableCityTokyo-2390-Large.jpg” /][et_pb_text admin_label=”Play community talk 2″ _builder_version=”3.15″]

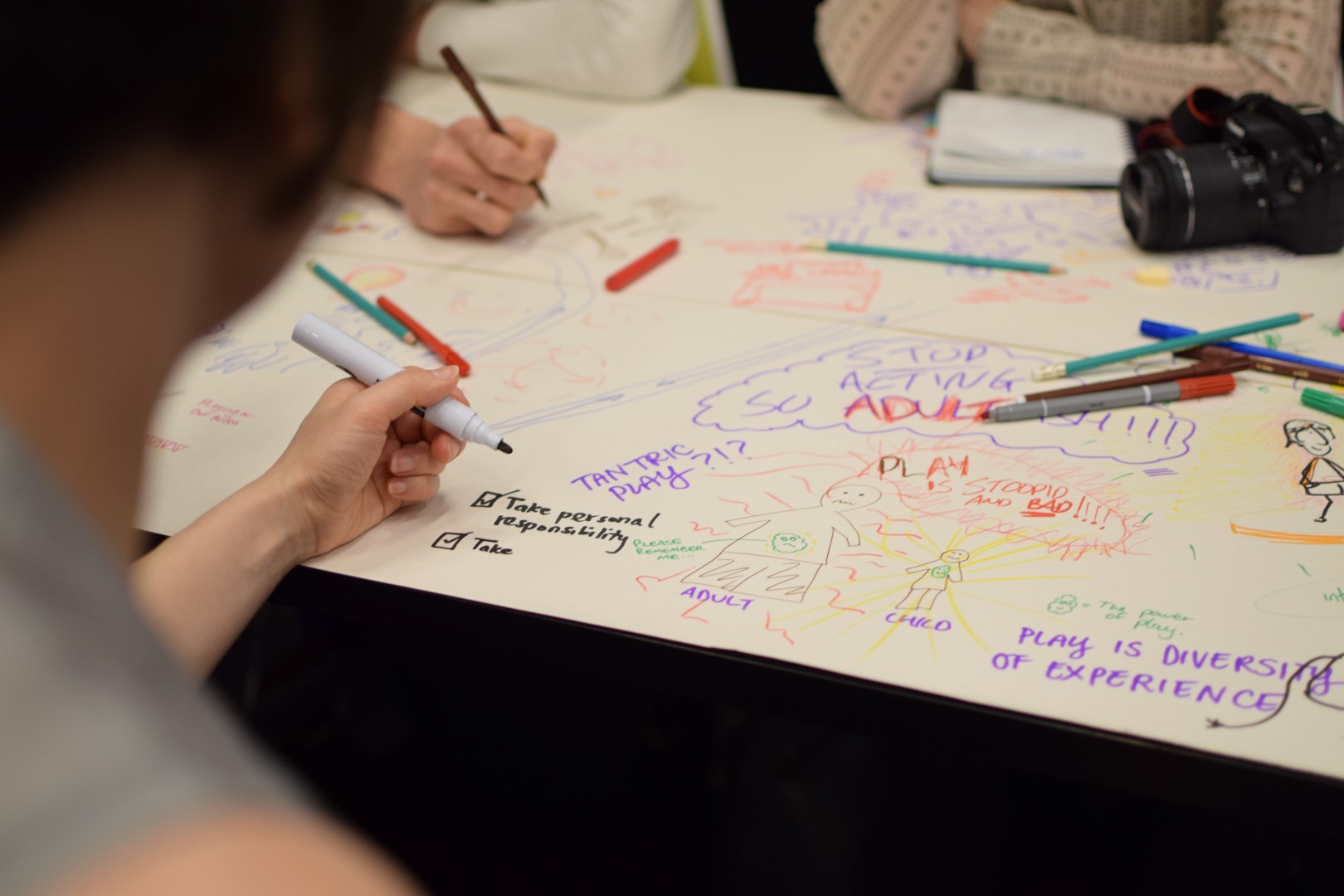

My most important message was to dare to be guided by play. To me, play is my one guiding principle. My compass. When I doubt what I’m doing, when I fear I’m moving in the wrong direction, I ask myself: ”what would play have done?”. ”Am I respecting the values of play?”. I have images of play in my head, the feeling of play in my body. I found myself talking as play as this imaginary friend, who I would always consult and ask for advice. “Am I doing this right?” Our manifesto is an attempt to describe how we see play, and I frequently revisit it, keeping me on the right track.

From here, you have to lead by example. Someone has to muster the courage to stand up and make a statement, demonstrating how play is not only permitted, but actively encouraged. You can do that, you can change the direction, the atmosphere, the culture, the rules. This is exactly what Clare Reddington and her partner in crime, Seiichi Saito, did when they were running around like this all day:

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image _builder_version=”3.15″ src=”http://www.counterplay.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PlayableCityTokyo-2399-Large.jpg” /][et_pb_text admin_label=”Play community talk 3″ _builder_version=”3.15″]

What does it mean to lead a community while being guided by play?

To name a few principles that are important to me, you have to embrace the diversity of play. There are as many ways to play as there are people on earth. Just like we should embrace diversity among people, we should encourage it in play. There is no right way to play, but there are many ways we haven’t seen yet. Play is uncertain and you shouldn’t try to eliminate that uncertainty. It’s not knowing what will happen in a moment that keeps play alive and vibrant, because anything might happen. Play is sincere and playing together, our mental barriers and facades fall away. We stop hiding and show who we really are. I’m pretty sure that if you’re not being sincere, if you don’t really mean it, the play community will wither and die. Finally, play is hugely generous. Play is not primarily about competing or winning, but about being in that moment together, keeping the play alive and everyone playing takes upon them part of the responsibility. This nurtures a generosity, where we care less about our personal needs and more about contributing to the shared experience. We have to be as generous to our play communities, also without always expecting anything in return.

Throughout all this, your efforts only ever really matter when you dare to trust the play community. If you do, they will perform magic. If you don’t, well, they won’t do much of anything. Trust is risky, intimidating, even. What if your trust is misguided? If those you trust will let you down? …but I honestly believe there is no other way to make play thrive (or to cultivate healthy societies, for that matter).

I ended with a few simple recommendations that might be helpful for anyone aspiring to cultivate local play communities:

- Create spaces for play to thrive – in our cities and our minds

- Start small – let play grow organically

- Be courageous – dare to experiment, embrace uncertainty

- Trust the play community

I will keep working for greater diversity in the play communities I’m part of, creating stronger ties across the globe, bridging gaps and bringing more people together. As for next year’s CounterPlay festival, there’s a call for proposals out now, and we’re working to get the play community much more involved in the process than ever:

https://twitter.com/mathiaspoulsen/status/1049721289391464449

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]